The ancient Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans all tracked the movement of time using a combination of a lunar calendar and various astrological records. The initial concept of tracking a seven-day period (a week) as part of time-keeping was introduced to Eastern Asia during the Tang Dynasty.

As the centuries have passed, four Chinese terms have become synonymous with the concept of a ‘day of the week‘, one of which (曜日 – yào rì ) is more ancient and is the root word underlying both the Japanese and Korean terms as well.

INTRODUCTION

In English, the names for days of the week are a combination of two terms, one a unique identifier (‘A’) and the other the word (‘day’) representing one seventh of a week. For example: Sun + Day

Similarly, China, Japan, and Korea all utilize a compound word with one unique identifier and their respective terms for ‘day of the week’.

“A” + “Day of the Week” (Japan & Korea)

“Day of the Week” + “A” (China)

The respective terms for ‘day of the week’ are rather complex, so we will start with the unique identifier (‘A’).

CHINA

The unique identifiers are relatively simple and predominantly are comprised of the Chinese numbers one through six.

| 一 | One | yī | Mon- |

| 二 | Two | èr | Tues- |

| 三 | Three | sān | Wednes- |

| 四 | Four | sì | Thurs- |

| 五 | Five | wǔ | Fri- |

| 六 | Six | liù | Satur- |

Sunday, the seventh day, is the only outlier but is relatively easy to recall. It uses the character ‘日’ (rì) which means ‘sun’ and is virtually a direct translation of ‘Sun + day”. A more informal way to say Sunday uses 天 (tiān) which means ‘sky’ or ‘heavens’, perhaps in reference to the fact that many religions worship on that day.

| 日 | Sun | rì | Sun- |

| 天 | Sky, Heavens | tiān | Sun- |

Having established the unique identifiers (A), it is time to go back and examine the first half of the ‘weekday’ equation (day of the week + A).

As mentioned previous, there are four ways to say the word ‘day of the week’ although China only uses three of them in current times.

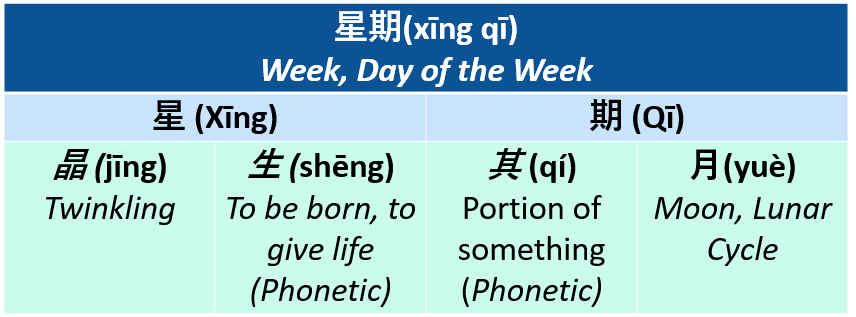

星期 (Xīngqī)

The first, “星期” or “xīng qī” is the more official term.

It is made up of two compound characters: first is 星 (comprised of a simplified combination of 晶 and 生) and second is 期 (a combination of 其 and 月).

星

Xīng

(tseeng)

Stars, Celestial Bodies

晶 (jīng), (a triplicate of 日 ‘sunshine’) that refers to something twinkling or sparkling + 生 (shēng) which generally refers to being born or giving life but here may just be a phonetic reference.

期

Qī

(Chee )

A Period of Time

Combination of 其 (qí) and 月(yuè). 月, as discussed with months, refers to the moon and lunar calendar. 其 (qí) has several meanings including ‘a portion of something (e.g., an interval, 其间)’. Here however, it seems to be phonetic. Together the terms refer to the changing of the moon, or an interval within the lunar month.

星期

Xīng qī

(Tsing chee)

Week, Day of the Week

Combining ‘a period of time’ with ‘stars, celestial bodies’

Writing the name of a day using 星期 (Xīng qī) is a simple matter of combining “星期” with the unique identifier (A):

星期 + Number (Monday through Saturday)

星期 + 日 (Sunday)

| Chinese | Romanized | English |

|---|---|---|

| 星期一 | xīngqī yī | Monday (Week + 1) |

| 星期二 | xīngqī èr | Tuesday (Week + 2) |

| 星期三 | xīngqī sān | Wednesday (Week + 3) |

| 星期四 | xīngqī sì | Thursday (Week + 4) |

| 星期五 | xīngqī wǔ | Friday (Week + 5) |

| 星期六 | xīngqī liù | Saturday (Week + 6) |

| 星期日 | xīngqī rì | Sunday (Week + Sun) |

周 (Zhōu)

A second, still formal, term for day of the week is “周” or “zhōu.” According to Improve Mandarin, this is a popular term amongst the more educated or urban social segments.

It apparently stems from an older Chinese term (週 or ‘shu’) which was adopted into Japanese Kanji and later reintroduced into more modern Chinese in the early 1900s. 週 (and now 周) refer to circling or surrounding; probably used as a reference to ‘cycle’ (e.g., the lunar cycle or the completion of a period of time).

周

zhōu

(joe)

Day of the Week, Week

Linked to the much older 週 or ‘shu’ which referenced a cycle or completed surrounding

Writing the name of a day using 周 (zhōu) is also a simple matter of combining “周” with the unique identifier (A):

周 + Number (Monday through Saturday)

周 + 日 [Sun] (Sunday)

| Chinese | Romanized | English |

|---|---|---|

| 周一 | zhōu yī | Monday (Week + 1) |

| 周二 | zhōu èr | Tuesday (Week + 2) |

| 周三 | zhōu sān | Wednesday (Week + 3) |

| 周四 | zhōu sì | Thursday (Week + 4) |

| 周五 | zhōu wǔ | Friday (Week + 5) |

| 周六 | zhōu liù | Saturday (Week + 6) |

| 周日 | zhōu rì | Sunday (Week + Sun) |

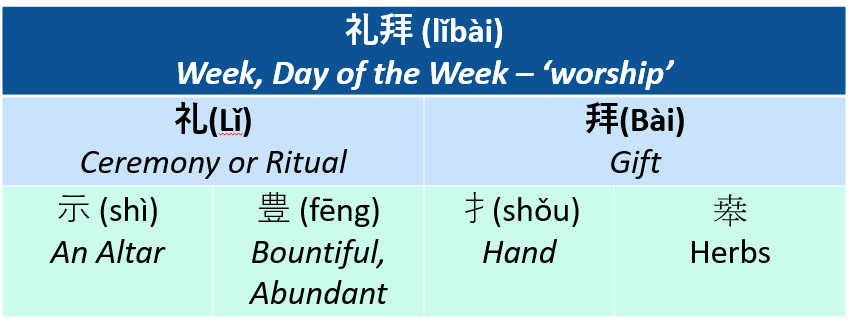

礼拜 (Lǐ bài)

The third, far more informal (though commonly used) term is 礼拜 (lǐ bài). The term is a combination of 礼 (lǐ) and 拜 (bài). 礼 (lǐ) is in turn a combination of 示 (shì) and 豊 (fēng).1 拜 (bài) is a combination of 扌(shǒu) and 𠦪 (unknown pronunciation).

Historically 礼拜 (lǐbài) referred to ‘worship’ and became linked to the concept of a week through the influence of religions such as Christianity and Islam who use a seven-day period to track the times for worship.

礼

Lǐ

(lee)

Ceremony or Ritual

Combines 示 (shì) representing an altar and 豊 (fēng) representing ‘bountiful or in abundance’ – e.g., a prayer or gratitude for abundance

拜

Bài

(bye)

To Give a Gift

Combination of 扌(shǒu) meaning ‘hands’ and 𠦪 (unkn. pron.) meaning herbs . . . to offer a gift

礼拜

Lǐbài

(lee bye)

Worship, Day of the Week, Week

Original meaning was ‘to worship’ (e.g., to offer up a gift in a religious ceremony) but became linked to the concept of a week due to religious influences.

As with the other two variations, this is is also a simple matter of combining “礼拜” with the unique identifier (A):

礼拜 + Number (Monday through Saturday)

礼拜 + 日 (Sunday)

| Chinese | Romanized | English |

|---|---|---|

| 礼拜一 | lǐbài yī | Monday (Week + 1) |

| 礼拜二 | lǐbài èr | Tuesday (Week + 2) |

| 礼拜三 | lǐbài sān | Wednesday (Week + 3) |

| 礼拜四 | lǐbài sì | Thursday (Week + 4) |

| 礼拜五 | lǐbài wǔ | Friday (Week + 5) |

| 礼拜六 | lǐbài liù | Saturday (Week + 6) |

| 礼拜日 | lǐbài rì | Sunday (Week + Sun) |

曜日 (Yào rì)

‘曜日’ or ‘yào rì’ is an ancient term that China itself no longer uses, but which heavily influenced the Japanese and Korean concepts.

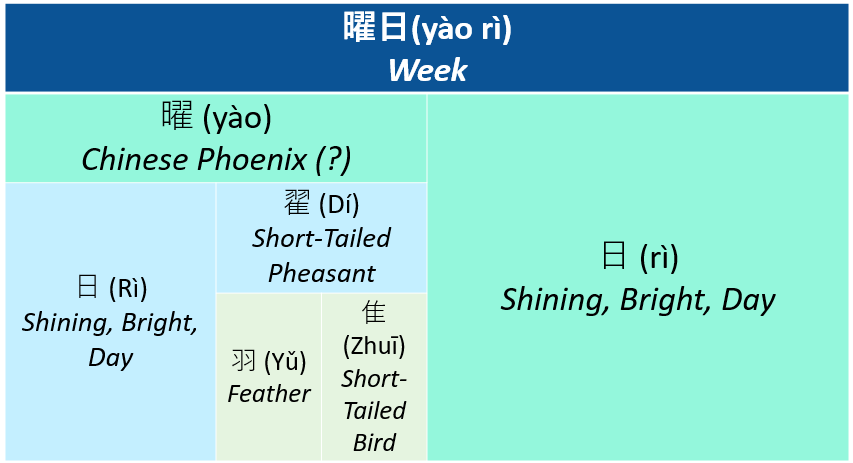

Th term is a combination of 曜 (yào), a complicated character made up of three smaller elements, and 日 (rì), a character representing the sun or a period of sunshine. A precise definition of the terms “曜” (yào) or “曜日” (yào rì) are difficult to find. Instead, I have attempted to work it out based on the elements making up the individual characters.

The Make-up of 曜 (Yào)

The character 曜 (yào) is made up of a combination of 日 (Rì) + 翟 (Dí); while 翟 (Dí) is itself a combination of 羽 (Yǔ) + 隹 (Zhuī)

日

Rì

(Ree)

Shining, Bright, Day

Originally a round circle with a mark in the center meant to resemble the sun. Now the square box with a line in the middle.

翟

Dí

(Dee)

Long-Tailed Pheasant

Suggests the addition of extra feathers (羽 – Yǔ) to a short-tailed bird (隹 – Zhuī) creates a long-tailed pheasant. These pheasants are common Chinese poetry and art.

曜

Yào

(Yow)

Chinese Phoenix (?)

By combining ‘sun + long-tailed pheasant’, they are apparently referring to the fenghuang or Chinese phoenix.2 This bird was thought to have the ‘wings of a swallow’ (amongst others) and originated out of the sun. It was a celestial creature with each part of its body representing different celestial bodies.

Ancient Chinese (曜日)

曜

Yào

(Yow)

Chinese Phoenix (?)

A celestial creature born of the sun with each part of its body representing different celestial bodies.

日

Rì

(Ree)

Shining, Bright, Day

Originally a round circle with a mark in the center meant to resemble the sun. Now the square box with a line in the middle. Also part of 曜 (Yào)

曜日

Yào rì

(Yow ree)

When the Sun is Shining Brightly

Perhaps similar to Apollo raising the sun with his chariot of fire, a day is the period when the sun shines brightly, a fiery phoenix soaring in the heavens.

- This could be pronounced “lǐ”, but the use seems to fit ‘fēng’ better ↩︎

- This is absolutely my own interpretation (IMO). I have not been able to find a good interpretation of what 曜 (yào) or 曜日 (yào rì) mean or why they are what they are. If you have a better explanation, please drop it in the comments! It appears to be a “sun” + “long-tailed pheasant” and looking up the terms brings up the fenghuang (Chinese Phoenix). This does make sense to me. . . the bird matches the description of the two terms (short wings like a swallow with extra special feathers, linked to the sun and other celestial concepts). I can see how they would connect the sun moving across the sky to a fiery bird soaring in the heavens. If I’m wrong, at least it makes sense in my trying to remember the characters 😂 ↩︎

JAPAN

Japan utilizes 曜日 (yào rì) as the root word for its version of ‘week’; including using the same Kanji characters (it still looks like 曜日). There are however three significant differences between the Japanese and Chinese vocabulary.

First, although it is spelled with the same characters (曜日), Japan has a slightly moderated pronunciation with “youbi” instead of “yào rì.”

曜日

-youbi or -yōbi

(yoh-bee)

ようび

-youbi or -yōbi

(yoh-bee)

Second, the Japanese write their combination of weekday names similar to that of English (A + ‘week’) or (A + youbi).

Third, Japan does not use the Chinese or Kanji numbers as unique identifiers. Instead, they utilize the more historical concept of using Kanji or Chinese words for various celestial bodies or astrological concepts (e.g., stars, moon).

Specifically, they start with week on Monday with the ever important moon (月), recalling the significance of the lunar cycle in their time keeping system. They end with the sun (日) on Sunday as well. The five days in between are each represented with one of the ancient five spiritual elements: fire, water, wood, metal (gold), and earth in that order.

From a learning perspective, it is not that hard to see how it went from ‘yào rì’ to ‘youbi’. I perhaps would try to remember “you be here on _________.” Recalling the meaning behind the names of the weekdays is not too difficult either once I have the order down (moon, fire, water, wood, gold, earth, sun). The pronunciation on the other hand is more of a case of simply memorizing. . .

*There are two ways to read Kanji (Chinese) characters in Japanese: on’yomi (the Chinese reading) and kun’yomi (the Japanese reading). This means the same character can have different pronunciations. Typically, I believe, the on’yomi pronunciation is used when it is a compound character (used with others to form a word) and the kun’yomi term is used when it stands alone.

In the examples below, the characters are going to be combined with ‘week’ to create the name of a day so the on’yomi pronunciation are used.

月 (getsu)

げつ

Moon 🌒

A full moon (original pictograph) that later morphed into a half-moon styled ‘ladder’.

Pronounced as がつ (gatsu) when used for ‘month’ (specific month, e.g., October), but pronounced as げつ (getsu) when used for a period of time (non-specific, e.g., one month). We use the second form here.

Pronounced In Chinese, it is pronounced ‘Yuè‘, so no help there 🤷♀️.

火 (ka)

か

Fire 🔥

A flame shooting up and flickering. Also looks like a person (人) with arms raised in fear (probably because there is a fire 🔥). May appear like this “灬” (logs burning) in some compound characters.

In Chinese, 火 (fire) is ‘huǒ’ which is a completely different pronunciation, so no help there 🤷♀️.

水 (sui)

すい

Water 🌊

A series of currents flowing downstream (original pictograph). The older pictographs are a little more obvious than the modern character. 🤷♀️ May appear as 氵or 氺 as a radical in some compound characters

It does sound like the Chinese ‘shuǐ‘ (water).

木 (moku)

もく

Tree or Wood 🌳

A tree with roots and branches pointing off the trunk.

Similar to the Chinese mù

金 (kin)

きん

Gold, Wealth 🪙

Two gold ore ingots being heated in an old kiln / oven.

“Jīn” in Chinese, which is pretty similar. Also sorta like ‘kiln’ 🪙

土 (do)

ど

Earth, Soil, Clay 🌷

Lump of clay on a potters wheel (original pictograph). Also resembles something growing up from the ground.

Sounds similar to and is sometimes read like the Chinese “tǔ”

日 (nichi)

(にち)

Shining, Bright, Day ☀️

Originally a round circle with a mark in the center meant to resemble the sun. Now the square box with a line in the middle.

| Kanji | Hiragana | Romanji | Identifier | Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 月 + 曜日 | げつ + ようび | getsu + youbi * | Moon | Monday |

| 火 + 曜日 | か + ようび | ka + youbi | Fire | Tuesday |

| 水 + 曜日 | すい + ようび | sui + youbi | Water | Wednesday |

| 木 + 曜日 | もく + ようび | moku + youbi | Wood | Thursday |

| 金 + 曜日 | きん + ようび | kin + youbi | Gold | Friday |

| 土 + 曜日 | ど + ようび | do + youbi | Earth | Saturday |

| 日 + 曜日 | にち + ようび | nichi + youbi | Sun | Sunday |

KOREA

Korea appears to have picked up the Japanese term ‘youbi’ as a borrowed word and are thus also rooted in the older 曜日 (yào rì). Unlike Japan, which continues to use the Chinese characters via Kanji, Korea uses the Hangul characters which are phonetic rather than pictographically based. The traditional Korean pronunciation of 曜日 (yào rì, youbi) is 요일 (yo il).

요일

(yo il)

(yo ill)*

Day of the Week

Based on the Korean pronunciation of

*It is slurred together when spoke and sounds to me more like “you’ll”? How do y’all hear it?

Korea places the day of the week at the end, using the pattern of (A + ‘day of the week’).

Like Japanese, Korea uses the same moon, fire, water, wood, metal, earth, sun) pattern for the unique identifiers; however, again they use the Hangul written form rather than the Chinese characters.

| Korean | Japanese | Chinese | Meaning | Day of the Week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 월 (wol) | 月 (getsu) | 月 (yuè) | Moon | Mon- |

| 화 (hwa) | 火 (ka) | 火 (huǒ) | Fire | Tues- |

| 수 (su) | 水 (sui) | 水 (shuǐ) | Water | Wednes- |

| 목 (mok) | 木 (moku) | 木 (mù) | Wood | Thurs- |

| 금 (keum)* | 金 (kin) | 金 (jīn) | Metal, Gold | Fri- |

| 토 (to) | 土 (do) | 土 (tǔ) | Earth | Satur- |

| 일 (il) | 日 (nichi) | 日 (rì) | Sun | Sun- |

The phonetic replacement of 日 (rì) with 일 (il) for Sunday is somewhat confusing as they do not sound much alike. That said, they do the same replacement in ‘day of the week’ where 曜日 (yào rì) is pronounced 요일 (yo il). As mentioned in the study of months, 월 (wol) is based on the Korean pronunciation of 月(yuè). Otherwise, the characters are generally quite similar to the Japanese pronunciation (e.g., ‘mok’ v ‘moku’). It is clear however that they are pulling their names for the five elements from Japanese rather than Chinese (‘mok’ is closer to ‘moku’ than ‘mu’ and ‘keum’ is closer to ‘kin’ than ‘jin’).

| Hangul | Romanized | Day |

|---|---|---|

| 월 + 요일 | wol lyo il | Monday |

| 화 + 요일 | hwa yo il | Tuesday |

| 수 + 요일 | su yo il | Wednesday |

| 목 + 요일 | mok il | Thursday |

| 금 + 요일 | keum yo il | Friday |

| 토 + 요일 | to yo il | Saturday |

| 일 + 요일 | il lyo il | Sunday |

Disclaimer

This website is absolutely not a professional resource and is purely my own personal way of trying to learn various languages. If you see a mistake, by all means please let me know in the comments as long as you do so in a friendly way. ❤️

Leave a comment